FURTHER DETAILS — FROM MAJOR CARLETON'S REPORT.

Prior to the publication of the foregoing story of the massacre repeated efforts were made to obtain a copy of Maj. J. H. Carleton's report of the tragedy made to the war department during the spring of 1859. Each effort was fruitless until the 29th of this mouth, when, by a fortunate incident, it was learned where the loan of a copy could be obtained.

In the compilation of the material from which the major made his report it became necessary to interview leading Mormons then residing in southern Utah; among whom was Jacob Hamblin, who has been sufficiently introduced to the reader. And inasmuch as the participants in the massacre had been enjoined to "keep silent" on the subject, and all Mormons were interested in shielding their "brethren" and their church from the odium of the crime, it was impossible to obtain the truth. As has been proved by Jacob Hamblin's evidence in the second trial of Lee, he knew every important detail of the crime, but in his interview with Major Carleton he placed the entire responsibility for the tragedy upon the Indians. When the latter were interviewed they denied the responsibility, but, like their Mormon friends, they were reticent as to the details of the crime and the identity of the participants.

It was only by analysis of the testimony of the Mormons and Indians whom the major interviewed, and noting the numerous contradictions, that he was able to justly charge the crime to the Mormon priesthood of southern Utah. Under such conditions it is a marvel that Major Carleton was able to sufficiently unravel the entangled web of falsehoods to enter even upon the confines of accuracy. Every important detail of the major's report, not given in the text of this story of the massacre, is given in the following excerpta, which will be highly appreciated because of the additional information regarding the personnel of the seventeen children saved from the slaughter.

The Author, October 31, 1910.

The Muddy river branch of the Pahute Indians, now residing on the reservation near Moapa, on the Salt Lake, Los Angeles & San Pedro railroad, were a murderous lot of savages at the time of the massacre. That, and the additional fact that their headquarters were more than 150 miles from the Mountain Meadows, doubtless induced the Mormons to implicate the Muddy Indians in the crime. During his determined efforts to get at the facts Major Carleton interviewed prominent men of that division of the Pahutes. They replied as follows:

"Where are the wagons, the cattle, the clothing, the rifles, and other property belonging to the train? We have not got or had them. No; you will find these things in the hands of the Mormons."

While camping at the Mountain Meadows, May, 1859, Major Carleton interviewed Mrs. Jacob Hamblin, who lived within two or three miles of the Meadows at the time of the massacre. Following is the major's report of the interview:

Mrs. Hamblin is a simple minded person of about 45, and evidently looks with the eyes of her husband at everything. She may really have been taught by the Mormons to believe it is no great sin to kill Gentiles and enjoy their property. Of the shooting of the emigrants, which she herself had heard, and knew at the time what was going on, she seemed to speak without a shudder, or any very great feeling; but when she told of the seventeen orphan children who were brought by such a crowd to her house of one small room there in the darkness of the night, two of the children cruelly mangled, and the most of them with their parents' blood still wet upon their clothes, and all of them shrieking with grief and terror and anguish, her own heart was touched. She at least deserves kind consideration for her care and nourishment of the three sisters (Rebecca, Louisa and Sarah Dunlap, the younger sisters of Rachel and Ruth Dunlap, whose pitiful fate has been detailed), and for all she did for the little girl, about 1 year old, who had been shot through one of her arms, below the elbow, by a large ball, breaking both bones and cuting the arm half off.

A few of the children saved from the slaughter were subsequently taken to the Indian farm at Corn creek, where, it is asserted, the emigrants had poisoned the water. One of those girls, named Elsie, so it is credibly reported, remained at Corn creek and later on became the wife of a highly respected stockman — a gentleman who was widely known in Utah. The other sixteen children were taken to Salt Lake City and delivered to Dr. Forney, United States Indian agent, who sent them to their relatives in Arkansas and other states. Of the personnel of the children Major Carleton reported as follows:

Sixteen of those were seen by Judge Cradlebaugh, Lieutenant Kearney, and others, and gave the following information in relation to their personal identity, etc. The children varied from 3 to 9 years of age, ten girls, six boys, and were questioned separately. The first is a boy named Calvin, between 7 and 8 years; does not remember his surname; says he was by his mother when she was killed, and pulled the arrows from her back until she was dead; says he had two brothers older than himself, named James and Henry, and three sisters, Mary, Martha and Nancy.

The second is a girl who does not remember her name. The others say it is Demurr.

The third is a boy named Ambrose Miriam Tagit; says he had two brothers older than himself and one younger. His father, mother and two elder brothers were killed; his younger brother was brought to Cedar City; says he lived in Johnston county, but does not know what state; says it took one week to go from where he lived to his grandfather's and grandmother's, who are still living in the states.

The fourth is a girl obtained from John Morris, a Mormon, at Cedar City. She does not recollect anything about herself.

Fifth, a. boy obtained from E. H. Grove; says the girl obtained from Morris is named Mary and is his sister.

The sixth is a girl who says her name is Prudence Angelina; had two brothers, Jesse and John, who were killed. Her father's name was William, and she had an uncle Jesse.

The seventh is a girl. She says her name is Frances Harris, or Horne; remembers nothing of her family.

The eighth is a boy too young to remember anything about himself.

The ninth is a boy whose name is William W. Huff.

The tenth is a boy whose name is Charles Francher (Fancher).

(Note,—Charles Fancher was the son of Capt. Charles Fancher, who was in command of the train, and was 11 years old. He was small for his age. He had a brother about 9 years of age, who was also small for his years, and which, no doubt, was the reason for their escape from the fate of those who were believed to be over 8 years old. Mormon children are baptised at 8 years, when, from the Mormon viewpoint, they reach the age of responsibility. Thus it was that the emigrant children under 8 years were not regarded by the Mormon priests as being responsible for the sins of their parents, who were murdered in obedience to the endowment oath to "avenge the blood of the (Mormon) prophets and martyrs." It was from the lips of Charley Fancher, soon after his arrival from the vicinity of the tragedy, that I heard the first story of the massacre. In his childish way he said that "some of the Indians, after the slaughter, went to the little creek, and that after washing their faces they were white men." During his stay in Salt Lake City I frequently played marbles with Charley Fancher on First South, a half block or so west of Main street. — The Author.)

The eleventh is a girl who says her name is Sophronia Huff.

The twelfth is a girl who says her name is Betsy.

The thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth are three sisters named Rebecca, Louisa and Sarah Dunlap. These three sisters were the children obtained from Jacob Hamblin.

I have no note of the sixteenth.

The seventeenth is a boy who was but 6 years old at the time of the massacre. Hamblin's wife brought him to my camp on the 19th instant. The next day they took him on to Salt Lake City to give him up to Dr. Forney. He is a pretty little boy and hardly dreamed he had again slept on the ground where his parents had been murdered.

It was twenty months after the massacre when Major Carleton encamped on the Meadows. His description of conditions will be interesting. He said:

The scene of the massacre, even at this late day, was horrible to look upon. Womens hair, in detached locks and masses, hung to the sage bushes and was strewn over the ground in many places. Parts of little children's and of female costumes dangled from the shrubbery or lay scattered about.

From Major Carleton's statement of the number of skulls and other human bones which lie gathered up and buried, it is evident that Jacob Hamblin's statement of the number of skeletons which he collected and buried was exaggerated, or that there were many more people in the company than has been heretofore estimated. And some of the bones were found a mile or so from the old camp ground, at points to which the coyotes had dragged them.

TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF JOHN D. LEE.

During the year 1875 Lee was tried for his part in the massacre. There were seven Mormons and five Gentiles on the jury. It was a mistrial. The Gentiles voted for conviction, the Mormons for acquittal. The wave of indignation that swept over the United States convinced the Mormon leaders that at least one Mormon must be sacrificed in the interest of their church. Haight and Higbee were hiding in the wilds of Arizona or Mexico. Klingensmith had taken refuge with a band of Indians in Arizona at a place on the south side of the Colorado river, opposite Eldorado canyon, in southern Nevada, where he took unto himself a squaw as his fourth or fifth wife. He voluntarily became a witness for the people during the first trial of Lee. He saved his neck, but lied with such facility that his evidence was of no value to the government, and after his discharge he returned to his wickiup on the Colorado.

The second trial of Lee occurred in September, 1876. The Mormon witnesses that could not be found during the first trial were easily located for the second trial, and became eager witnesses on every feature of the evidence that was necessary to convict John D. Lee. But the attorneys for the government found it impossible to awaken the slumbering memories of the elders of any evidence that would convict others of the assassins.

Another significant feature of the trial was that the marshal who subpoenaed the jurors must have received a "hunch," for he secured as many Mormon jurors as the law permitted.

It was believed by the marshal who had charge of the arrangements for Lee's execution that if the Mountain Meadows were selected as the place for the final ordeal that the condemned man might, on the tragic ground, be induced to make a statement of the inside facts which would enable the representatives of the government to work more intelligently in the matter of bringing other guilty men to justice.

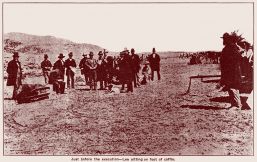

It was about 10 a. m., March 23, 1877, when Lee and his executioners arrived at the Meadows. Photographer James Fennemore of Beaver, where Lee was tried; Josiah Rogerson, a Mormon telegrapher; a number of newspaper correspondents, including S. A. Kenner of the Deseret News, and a small number of spectators were present.

Prior to the execution Lee accompanied the marshal and a number of those present over the field and pointed out the respective localities of chiefest interest. But no useful information was divulged.

Lee's coffin was brought from the wagon and placed near the mound of stones which cover the remains of the emigrants.

A covered wagon was drawn up to within a few paces of the coffin. Five holes had been made in the cover, and five men were seen to disappear within the wagon.

Standing near his final receptacle, Lee made a brief farewell speech in which he denied any intent to do wrong. He claimed, and rightly, too, that he had been betrayed — sacrificed in the interest of the church to which he had given his whole life. Continuing, the doomed man said:

Still, there are thousands of people in this church that are honorable and good hearted friends, some of whom are near to my heart. There is a kind of living, magnetic influence which has come over the people, and I cannot compare it to anything else than the reptile that enamores its prey till it captivates it, paralyzes it, and it rushes into the jaws of death. I cannot compare it to anything else. It is so. I know it. I am satisfied of it.

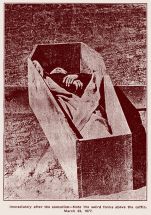

Lee's vision swept the scene of former carnage. He looked out on the repulsive ridge from which had been poured the deadly missiles into the emigrant camp. Furtively he glanced at the monument erected by Major Carleton. Mortals will never know the thoughts that, with torrential confusion, leaped through the brain of the doomed man as he sat down on his coffin for the crucial ordeal. He asked that his arms be not pinioned, and that his eyes be not bandaged. The first request was granted. United States Marshal William Nelson fastened a handkerchief over Lee's eyes, then stepped to one side. Lee clasped his hands over his head and said to the marshal: "Let them shoot the balls through my heart! Don't let them mangle my body!"

The marshal called "Ready, aim, fire!" A sharp, simultaneous explosion, and the victim of unquestioning obedience had paid the mortal demand for vengeance, had satisfied the doctrine of human justice!

Lee was the husband of nineteen wives, one of whom, however, was a "spiritual" wife. By eighteen of his wives he had sixty-four children, fifty-four of whom were living at the time of his death.

His last wife, Ann Gorge, was married to him by Heber C. Kimball about 1865, which created considerable gossip among the Saints of southern Utah where every incident of the massacre was well known. And it will be proved by the evidence of Jacob Hamblin, given at Lee's second trial, that Brigham Young and his second counselor, George A. Smith, knew every detail of the massacre which was known to Jacob Hamblin, and he knew all of the facts and the name of every prominent participant within a very short time after the occurrence of the tragedy.

At the time of Lee's interview, on September 29, as proved in the appendix herewith, Lee told President Young that there was "not a drop of innocent blood in the company" of emigrants. If no "innocent blood" was shed at the Meadows, under the "revelation" on plural marriage given to the first "prophet," then was John D. Lee and the other assassins guiltless before the Mormon god, and there was no obstacle in the way of Lee and Haight taking more plurals after the massacre, and becoming members of the Utah legislature. Indeed, the addition to their harems of more plurals was, according to the polygamy ''revelation," a certain means of salvation and exaltation. Under the teachings of that "revelation" the debauching and murder of the Dunlap girls was no bar to the highest exaltation in the Mormon "celestial kingdom of God"! Paragraph 26 of the "revelation" reads as follows:

Verily, verily I say unto you (Joseph Smith), if a man marry a wife (or wives) according to my word, and they are sealed by the holy spirit of promise, according to mine appointment, and he or she shall commit any sin or transgression of the new and everlasting covenant whatever, and all manner of blasphemies, and if they commit no murder, wherein they shed innocent blood — yet shall they come forth in the first resurrection, and enter into their exaltation....

For further details and particulars regarding the culpability of the leaders of the Mormon church, the reader is respectfully referred to the appendix herewith.