THE DOOMED ARKANSAS COMPANY.

Little is known of the personnel of Fancher's company. No doubt the larger number was from Arkansas. There were many from Missouri, and a few from other states.

William Eaton, whose niece is living in Salt Lake City, was a native of Indiana. During the early fifties he went to Illinois, where he secured a farm. Early in 1857 he met some men from Arkansas who were visiting relatives in Illinois preparatory to moving to California with the Fancher company. Eaton sold his farm, took his wife and little daughter back to Indiana, and joined the company in Arkansas. The last letter received by Mrs. Eaton from her husband stated that all was well, but subsequently she learned that the company had been exterminated.

William A. Aden, another of the victims, was born in Tennessee, and was about twenty years old at the time of the massacre. A recent letter from his brother, James S. Aden of Paris, Henry county, Tennessee, states that his brother was an artist, and relates an interesting incident that occurred in Paris several years prior to his brother's departure for California, and which forms the basis for another interesting incident at Parowan, Utah.

William Laney, a Mormon elder from Utah, was proselyting in the vicinity of Paris. He secured the courthouse and proceeded to expound Mormonism. A number of mischievous lads, among whom was William A. Aden, pushed a small cannon to the rear of the courthouse, and while Elder Laney was preaching the boys discharged the small piece of ordnance. Elder Laney thought that an armed mob was upon him. He abruptly discontinued his discourse, ran from the building and sought safety in hurried flight. On his mad race out of town he met the father of young Aden, who took him home and cared for him during the elder's stay in the vicinity.

Early in 1857 young Aden left Tennessee for California. He sketched scenery along the route, and on his arrival in Utah went on to Provo, about 47 miles south of Salt Lake City, where he did some scenic painting for the Provo Dramatic association. On the arrival of the doomed Arkansas company he joined them and went on to the Mountain Meadows.

Frank E. King and wife traveled with the Fancher company from Pacific Springs, Wyoming, to Salt Lake City, where, owing to the sickness of Mrs. King, he was compelled to remain until December 4, when he went on to Beaver, 210 miles south of Salt Lake City, and thus escaped the fate that lurked for the company in southern Utah.

The author of this story of the massacre is indebted to Mr. Frank E. King for much interesting data relative to the company, and of his experience in Utah about the time of the massacre, and will, therefore, introduce him more fully to the reader.

On Mr. King's arrival in Beaver the bishop of the ward advised him to remain during the winter as the Indians, after the massacre, were more than usually hostile toward Gentiles. Mr. King remained during the winter, and, notwithstanding the friendliness of the bishop, was twice ordered to move on by some of the fanatics. On May 15 Mr. King again started for southern California, and reached Cedar City on the 17th. Quoting from Mr. King's letter, he says:

I had not unhitched my team when John M. Higbee and Elias Morris, second counselor to Isaac C. Haight, ordered me to leave before the sun rose the next morning.

Mr. King regarded the order as ominous, and returned to central Utah. After living in Manti and other towns he joined the first colony of settlers in Marysvale, Piute county, Utah, where he resided until some five years ago, when he moved to Grant's Pass, Oregon.

Although the writer's intimate acquaintance with Mr. King extended over a period of twenty-five years, I never heard him mention the Mountain Meadows massacre, and knew nothing of his association with the unfortunate company until his son, Charles, who resides in Marysvale, last Winter (1910) told me that his father traveled in Fancher's company. Soon after the discovery I wrote to Mr. King and received some of the information which is used in this history of the massacre.

There were certain questions in dispute, and with my first letter to Mr. King I inclosed a list of questions which, with the answers, are given herewith:

Ques.— Kindly give the names of as many members of the company as you can remember?

Ans.— Fancher, Dunlap, Morton, Haydon, Hudson, Aden, Stevenson, Hamilton, a family by the name of Smith and a Methodist minister.

Ques.— Give the Christian names of the two Dunlap girls and their ages?

Ans.— Rachel and Ruth, aged sixteen and eighteen years, respectively.

Ques.— How many wagons and carriages in the train?

Ans.— Forty.

Ques.— How many men capable of bearing arms, and about how many women — married and single, large girls included?

Ans.— About sixty men, forty women and nearly fifty children.

Ques.— About how many horsemen in the train?

Ans.— About twelve, as near as I can remember.

The settlements in Iron and Washington counties were less than six years old, and distant 240 to more than 300 miles from Salt Lake City. Mail lines had not been established. All communication with Salt Lake was necessarily by special messenger or by the slower means of those who occasionally went to and fro on business. At the time of which we are writing the people of those remote southern settlements were in the throes of the Mormon "reformation," and the news of the approach of Johnston's army served to intensify the frenzy. They had three years' breadstuff on hand, but were continually urged to husband it for the expected "big fight" with the United States.

PERSONNEL OF THE LEADING ASSASSINS.

Isaac C. Haight resided in Cedar City, about 260 miles southwesterly from Salt Lake City, and forty miles northeasterly from the Mountain Meadows. He was president of the Parowan "stake of Zion," and as such was the ecclesiastical agent in Iron county of President Brigham Young. to whom all the presidents of "stakes" reported, and to whom they were directly responsible for their acts. Haight was also lieutenant colonel in the Iron county militia, and upon him must ever rest the larger part of the odium for the inception and details of the massacre.

As bishop of the Parowan ward of the Parowan "stake of Zion,'' William H. Dame was under the ecclesiastical direction of President Haight. But as colonel in command of the military district comprising Iron and Washington counties Dame was the military superior of Haight.

John M. Higbee resided in Cedar City, was first counselor to Isaac C. Haight in the Parowan "stake of Zion," and was major in the Iron county militia.

The practice of conferring ecclesiastical, civil and military powers on the same individual has been a distinguishing feature of the Mormon church from its beginning in 1830. Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, was at once the representative of the Mormon god upon the earth, mayor of Nauvoo, and lieutenant general of the Nauvoo legion. And just before his death in 1844, the Mormon "prophet" was nominated for president of the United States by the Democrats under his spiritual control. And it is an inexorable law that the ecclesiastical power of the Mormon hierarchs is superior to that of the civil and military divisions, or adjuncts, of the church.

And there is no doubt that Dame reluctantly became an abettor of butchering the emigrants because of the fact that Haight was his ecclesiastical superior.

There is a popular and widespread impression that John D. Lee was the leader and arch criminal of the massacre. That is not true. He held no special office in the priesthood, but was farmer to the Indians under Superintendent Brigham Young. Lee was a man of medium height, heavy build, and possessed more than average intelligence. As an abject slave of the Mormon priesthood he was a willing tool of his "file leader" in deeds of violence. Lee's father was a member of the "First Families of Virginia," and had not the son become tainted with Mormon superstition, and the victim of the fatuous doctrine of unquestioning obedience to the self- constituted vicegerents of God, he would doubtless have lived and died an honored member of society.

Philip Klingensmith was bishop of the Cedar ward and Samuel McVurdy was his first counselor.

Except in so far as it is necessary in the discussion of the details of the tragedy, it would be an act of wanton cruelty to name the others of the fifty-five white men who were present at the massacre. The public naming of those men would serve no purpose, and would add unnecessary weight to the cross which hundreds of their innocent descendants are bearing.

The great majority of the men who participated in that almost unparalleled crime were not murderers in the generally accepted definition of the word. They were irresponsible victims of gross superstition, and, almost without protest, they stained their souls with blood in the effort to perform the will of God, as they understood the order to commit murder. The execrations of those now living, and of those who will read the story of the tragedy at the Mountain Meadows in the years to come should fall upon those who taught the doctrine of unquestioning obedience and blood atonement, and upon those present day "prophets, seers and revelators" who teach that a Mormon "lies in the presence of God" when he declines to surrender his temporal being to the representatives of an alien and despotic priesthood.

Such were the people, and such were the conditions that awaited Captain Fancher's company of one hundred and fifty souls.

It was about the middle of August, 1857, when the Arkansas emigrants emerged from Emigration canyon and camped on Emigration square, the present site of the Salt Lake city and county building.

After laying in such supplies as could be obtained in Salt Lake City the emigrants proceeded southward, following the well beaten road that stretched out southerly and then southwesterly to southern California.

According to Mr. Frank E. King the company was short of supplies when they left Salt Lake. At Nephi, about 100 miles south of Salt Lake, they made the attempt to purchase flour of "Red Bill" Black, who ran the flour mill, but were peremptorily refused. A like effort was made at Fillmore, sixty miles south of Nephi, and with like results.

At Corn creek, fourteen miles southwesterly from Fillmore, the emigrants laid over a day or two to permit their work animals and cows which they were taking to California to graze on the then luxuriant pasturage of that locality. During their sojourn at Corn creek one of the emigrants' animals died. A portion of the carcass was eaten by some of the Pahvan Indians, who yet have an encampment near the creek. It is reported that four of the Indians died, presumably from the effects of eating the diseased meat.

That incident has been worn threadbare by Mormon and pro-Mormon historians, who charge that the emigrants poisoned the carcass for the express purpose of killing some of the Indians.

And those same historians also assert that, as an act of revenge, the Indians followed the emigrants to the Meadows and there exterminated them. Those historians also charge that the emigrants poisoned the water of a spring with the purpose, as is alleged, of killing more Indians. The second charge will receive first attention.

The nearest spring is a half mile or more north of where the emigrants were camped, and twice that distance from the old camp ground of the Indians. The spring is in the nature of a slough in soil highly charged with alkali, of which the water contains an appreciable quantity. Not even an Indian would drink the water from that spring while the pure mountain water of Corn creek was within a few rods of where the Pahvans were camped. It would have required many pounds of poison to have been effective on life, and the emigrants would have poisoned their cattle, which were grazing on the bottom land near the slough.

The emigrants were well within that section of Utah where the Indians were periodically at war with the Mormons, and which continued until the close of 1866. The Pahvan tribe was strong and restless. Less than four years previously Moshoquop, the war chief of the Pahvans, and a fraction of his band murdered Lieutenant Gunnison and his exploring party of nearly a dozen men as an act of revenge for the killing of Moshoquop's father by a hot headed emigrant.

The Fancher company was not an aggregation of fools or lunatics. They knew that they were within the power of an enemy that was then preparing for war with the United States. Their failure to obtain food supplies, and the sullen behavior of the Saints would have convinced men of ordinary sense and caution that theirs was a dangerous situation. And they knew that scores of places, like the defile known as Baker's pass, not twenty miles away, where a dozen Indians could waylay and murder a hundred men, must be traversed before they could reach the open country of the Nevada deserts.

And at the second trial of John D. Lee, in 1876, Nephi Johnson, a devout Mormon and Indian interpreter, forever disarmed the lying Mormon historians by declaring that no Pahvan Indians were present at the massacre. A portion of Johnson's evidence, as also that of other witnesses, is given in the appendix at the close of this narrative.

The fact is, western Indians, when pressed for food, eat the flesh of diseased animals; and that the Pahvans knew that the emigrants were blameless in the matter of the death of four of their braves is abundantly proved by the fact that they did not molest the strangers.

At Beaver, about forty-eight miles from Corn creek, the emigrants made another unsuccessful attempt to purchase supplies.

On their arrival at Parowan, thirty miles south from Beaver, the emigrants encamped outside the "fort" or earth wall surrounding the Mormon residences and gardens. By some means the emigrants succeeded in purchasing a small quantity of wheat, but there was no mill in the settlement.

Among those who visited the camp of the emigrants was Elder William Laney, who has before been mentioned as a missionary in Tennessee. William A. Aden immediately recognized Elder Laney as the man whom he, with other boys, had frightened by the discharge of a small cannon in the rear of the courthouse at Paris. Aden at once made himself known to the elder, who recollected that Aden's father had given him shelter when he believed that his life was in danger, and cordially invited the young Tennesseean to visit him within the fort. Aden accepted the elder's hospitality and visited his home where Elder Laney had two wives living in the same cottage. Aden noticed that the elder had a fine patch of onions growing in his front yard and asked to purchase some of them. Elder Laney called his wives and instructed them to pull the onions for Aden. The onions were presented to the son of Laney's benefactor in Tennessee. For that slight act of reciprocal kindness the bishop of Parowan sent two young men by the name of Carter to Laney's house. The latter was called out to the sidewalk where one of the young thugs beat him into insensibility with a club. Laney's wives dragged him into the house and protected him from further assault by the emissaries of the Mormon priesthood. Laney's injuries affected him during the remainder of his life. The incident serves to illustrate the fanaticism and hatred that inspired the Saints to commit the final act of extermination of the emigrants.

From Parowan the road turns sharply to the southwest, and thus continues eighteen miles to Cedar City, where the emigrants made another ineffectual effort to purchase provisions. But Joseph Walker, who was running the flour mills, ground the wheat which had been obtained at Parowan. Bishop Klingensmith sent an elder to Walker and ordered him not to grind the wheat. The sturdy and bluff old Englishman said to the bishop's agent: "Tell the bishop that I have six grown sons, and that we will sell our lives at the price of death to others before I will obey his order." During many weeks after the incident the emissaries of the bishop hounded Walker, and one night while at work in the smutting room of the mill he saved his life by blowing out the candle, thus thwarting the assassins who were lurking near the window of the room. And although Joseph Walker knew by whose orders, and by whom, the Mountain Meadows massacre was perpetrated, he lived and died a Mormon. Once thoroughly converted to the belief that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God, a little thing like the massacre at the Meadows doesn't even jar the faith of the average Mormon.

It is very likely that the emigrants had neglected to apply at Salt Lake City for "permits" to pass through the territory of the United States. They were American citizens, pioneers of Arkansas and Missouri, and were not accustomed to asking for permits to travel the public highways. If defenders of the Mormon "prophets" accept the theory that Brigham Young's "proclamation" declaring martial law was not in effect at the time the emigrants were en route to the Meadows, and that "permits" were not necessary, they abandon the only possible excuse, or apology, for the massacre — that under all the circumstances it was a military necessity, and must, forsooth, concede that it was a religious murder and that "by their fruits ye shall know them."

Cedar City was the last town on their route to California, and the last place where Brigham Young's order regarding permits could, without a massacre, be enforced. And "Brother" Isaac C. Haight was the last man on the route who was "authorized" by the Mormon "prophet" to issue permits. And there is no doubt that Haight insisted that the orders of his religious master in Salt Lake City be fulfilled to the letter, and that the emigrants resented the insult.

Whether true or false, unfortunately the emigrants cannot be called in rebuttal, the Mormons of Cedar City have been insistent in their charges that the emigrants' conduct was rude, defiant and boisterous. It is alleged that they fired their pistols in the air, "swore like pirates," and defied the town authorities to arrest them. It is also asserted that some of the emigrants from Missouri boasted of having aided in driving the Mormons from that state, and with having helped kill "old Joe Smith" at Carthage jail in Illinois. It is also affirmed that the emigrants swore that they would take provisions by force from the small hamlets and ranches through which they expected to pass on their way down the Santa Clara river.

Fancher's company turned westerly, following the old emigrant trail to California, and camped at the southwest corner of the Cedar co-operative field. According to Mormon statements, it was there that the emigrants committed their last depredation, although they passed through Pinto, six miles northeasterly from the Meadows. According to rumor, they used some fencing for fuel, thus opening the Cedar field to the trespass of range cattle and horses.

The emigrants were then about thirty miles northeasterly from the Meadows. We will precede them and make the reader acquainted with the topography of the locality.

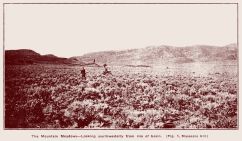

The Mountain Meadows are situated about twenty-five miles southeasterly from Modena, a distributing station on the Salt Lake, Los Angeles & San Pedro railroad, in the southwesterly part of Iron county.

A few miles north of the Washington county line the land rises quite rapidly to the southwesterly "rim of the Great Salt lake basin." Beginning at the "rim," and descending gently toward the southwest some two miles, is a narrow valley or depression similar to scores of others which occur in the higher altitudes of the Rocky mountains. A low, undulating bench, occupied by sparsely growing scrub cedars and pinyon pines, forms the eastern boundary of the depression, while low hills and ridges roll away toward the west a mile or so, where they vanish in the east base of the Beaver Dam range of mountains.

The locality is about 6000 feet above sea level, and fifty years ago the narrow strip of bottom land was covered with luxuriant high altitude grass. With the exception of clumps of scrub oak and scattering cedars on the hillsides, there is nothing to relieve the monotony of the bare hills and ridges. A few springs weakly emerge from the hillsides and bottom land and furnish all the water within a distance of several miles. Well down toward the lower end of the depression a small spring emerged from the sward within about thirty yards to the southeast of where the emigrants went into camp for the last time. To the west, and within twenty rods of the spring, the south end of a low ridge rises from the flat and reaches out a quarter mile or so toward the north. The crest of the ridge is strewn with blocks of basalt, and forms a natural rampart. The base of the eastern hillside is not more than thirty rods from the spring, and is occupied with clumps of oak brush.

About thirty rods northeast of the old camp grounds is a comparatively high hill of small dimensions, from the base of which a low swell, or rise of ground, extends southerly to the bench. To the south and east of the swell, a few rods from its summit, is a depression covered with a dense growth of mountain sage. Across the depression, some thirty rods to the south, the base of the bench is bounded by a gully some twelve feet deep — deeper now than at the time of the massacre. The south side of the gully is conspicuously marked by two large clumps of scrub oak, and beyond the hillside is occupied with sage, scrub oak and scattered cedars. The east clump of oak was the scene of the most terrible incident of all that heartless butchery.

Although the rights were somewhat chilly in the high altitude of the meadows, the days were quite warm, and the emigrants knew that three or four days' travel would take them down into an altitude of about 1500 feet, and out on the blistering sand and gravel strewn plains and mesas of southern Nevada, where, in some localities, the watering places are fifty miles apart, and scant forage for animals. Doubtless those considerations again prompted them to rest their cattle for the hard journey that awaited them. And had conditions been otherwise they were really conserving time and comfort in the delay.

About September 7, or the Sabbath following the departure of the emigrants from Cedar, a meeting of the priesthood was held in the combined school and meeting house on the public square.

There had been hatched in the cruel, priest-ridden brain of Isaac C. Haight a plot to exterminate the emigrants. His scheme was to collect the Indians within a radius of sixty miles and loose them upon the strangers, and he would put the question to the brethren at the meeting. He was already assured of the enthusiastic support of Bishop Klingensmith.

The subject of the extermination of the emigrants was duly presented to the priesthood (nearly every man in the Mormon church holds the priesthood), and was discussed at considerable length. A few of the elders opposed it, while others warmly approved the measure that was so in harmony with the teachings of the "prophets" and with the "spirit of the reformation." The arguments waxed warm and caused considerable commotion.

While the excitement was at its height a commanding figure entered the building. The man was Laban Morrill, who presided over the spiritual and temporal welfare of the Saints at Johnson's Fort, a small settlement about six miles northerly from Cedar. Laban Morrill would have attracted attention anywhere among his fellowmen. His fine head, strong, yet kindly features and dignified bearing marked him as an altogether superior man. After seating himself Mr. Morrill turned to an elder and asked him the cause of the excitement.

After listening a few minutes to the speeches for and against the measure, Laban Morrill arose and dispassionately pointed out the unwisdom. and inhumanity of the proposed deed. President Haight and Bishop Klingensmith contended for the perpetration of the infamous crime. They urged that the Lord's prophet had said: "If any miserable curses come here, cut their throats." It was not advice, it was a command. And the emigrants surely came within the meaning of the term "miserable curses." Had they not boasted of having aided in driving the "Lord's chosen people" from Missouri? And had they not also boasted of helping to murder the Lord's greatest prophet, Joseph Smith? And had they not also threatened to raise an army in California and aid in exterminating the Mormons?

Such were the arguments used by Haight, Klingensmith and others to, inflame the passions of the elders, and to "keep alive the spirit of the reformation," as President Young had advised. But the masterful presence of Laban Morrill, for the moment, apparently stood between the emigrants at the Meadows and destruction. The discussion was long and stormy, but Morrill finally forced an apparent compromise. He described the ineffaceable stain that such an infanmy would bring upon the church, and upon the descendants of those who participated in the crime. As a last, and more forcible, argument he told the elders that President Young had not been consulted in the matter. It was then agreed that action be deferred until reply could be received from a message that would be sent the next day to President Young. With that understanding the elders dispersed, and Laban Morrill returned home "feeling," as he subsequently expressed it, "that all was well."

It was nearly dark of an evening some three or four days prior to the priesthood meeting just described, when President Isaac C. Haight walked out on the public square at Cedar City. Evidently he was expecting someone. He had but a few minutes to wait.

A man of medium height, heavy build and square, smooth face rode up and dismounted. After the usual greetings, and a compliment to the newcomer for his promptness in responding to the summons, Haight told Lee that he had an important matter to discuss with him, and suggested that they take some blankets and spend the night in the unused iron works building (subsequently used for a distillery), where they would not be disturbed.

During the night the plot for murdering the emigrants was fully discussed, and the details, so far as possible, were arranged. Nephi Johnson, a youth of nineteen years, and an excellent Indian interpreter, was selected to "stir up" the redskins in the vicinity and send them down to the Meadows. Johnson was to represent to the Indians that the "Mericats" — Gentiles — were at war with the Mormons and Indians, and that the emigrants were going to California with the avowed purpose of returning with an army to exterminate the Mormons and Indians. Carl Shirts, Lee's son-in-law, was assigned to a like mission among the Indians near St. George, and Oscar Hamblin was to lead the Santa Clara Indians to the Meadows.

To those not acquainted with the inner workings of the hierarchal despotism called the Mormon church, it may appear incredible that Nephi Johnson and the others would consent to become tools in a scheme so diabolical, so cruel and inexpressibly treacherous, but the facts to be related will remove the last doubt. Subsquently, Nephi Johnson testified that he was afraid of personal violence if he refused, and that he had known of instances where men had been "injured" for refusal to do as they were told. By an ingenious ruse, at the last moment, Johnson avoided personal participation in the wholesale murder.

The afternoon following the priesthood meeting James H. Haslam, now residing in Wellsville, Cache county, Utah, started on his memorable ride to Salt Lake City, bearing the message of inquiry as to the disposal of the emigrants. The story of that ride, of the relays of horses, of the delay because of the indifference of the bishop of Fillmore, and of other incidents would be interesting, but regard for brevity compels their omission.